We drove from Vimy, France, to Ypres, Belgium

Ypres

The City with Many Names

Ypres is a city in the province of West Flanders in Belgium. It is called Leper in Flemish (pronounced eep-er.) In French, it is Ypre (pronounced eep-rah). In English, it is Ypres (pronounced eep-ray). During the First World War, the soldiers did not know how to pronounce the name, so they called it Wipers (pronounced wipe-ers). Almost everyone here speaks English as well as Dutch and French. I have not met a single person who could not speak English.

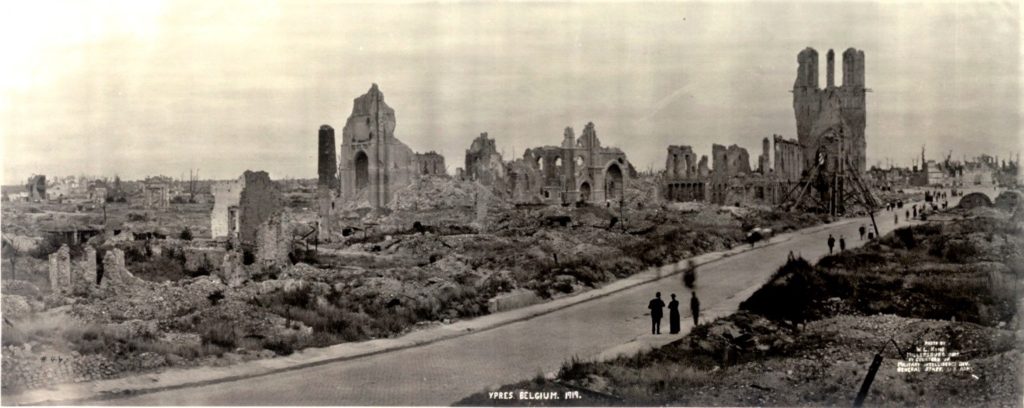

Ypres is an ancient town. It was there during the Roman invasions in the first century. During the middle ages, Ypres was famous for its cloth exports. The beautiful Cloth Hall was built in the 13th century. It was used as a meeting place for the Cloth Guild as well as storage and sales of cloth (not manufacturing, which was done at other sites).

The whole city of Ypres was destroyed during the First World War. In the 1920s, the city was rebuilt exactly as it was before the war. Today, the Cloth Hall holds an excellent museum of WW1 as well as a local city museum, the visitor’s information centre and a book and gift shop. This should be your first stop in Ypres.

History

Over the centuries, Ypres was attacked by Rome, England, France and Austria. This was nothing compared to the disaster that befell the town during the First World War. Ypres had the unfortunate luck of being in the middle of the contested area during the Battle of Paschendale. Belgium was a neutral country then, but that did not stop the Germans from invading. Britain was an ally of Belgium, so this invasion brought Britain into the war. With the British, Canadians, Australians and New Zealanders on one side and the Germans on the other, poor Ypres was caught in the middle. The belligerents fought over Ypres and Passendale from 1914 to 1918 in horrifying battles that left desolation and 185,000 Allies dead. The British Empire troops defended Ypres Salient from October 1914 to the war’s end.

Three great battles were fought over Ypres and the surrounding area, including the nearby village of Passchendaele. The First Battle of Ypres occurred from 19 Oct to 22 Nov 1914. The second battle was from 3 Jan 1915 to 25 May 1915, during which the Germans fired chlorine and mustard gas at the allies. The Third Battle of Ypres was the largest and the worst. It occurred mostly near the village of Passchendaele and is sometimes known as the Battle of Passchendaele. This battle raged from 31 July to 6 Nov 1917.

Between these massive and horrendous battles, the troops on both sides settled into static trench warfare, where the lines did not move for months at a time. Yet, throughout it all, the British Empire troops manage to defend and occupy Ypres for the entire war.

Throughout the war, the Allies pushed the Germans back. But in the final battle, the Germans re-captured all the land they had lost and were almost to the gates of Ypres. British, Canadian, Australian, and New Zealand troops held Ypres but at a great cost. There were half a million casualties in total to all countries involved. During this battle, the town of Ypres was totally destroyed.

By the war’s end, there was barely a building or a tree in the Ypres Salient. 1917 had been the wettest in more than 70 years. The rain and the artillery left the area nothing but mud and craters. And it was all for nothing. In early October 1918, the Germans and the Allies were basically at the same location as at the beginning of the war.

In October 1918, the Germans finally retreated, and the front line moved on, leaving the Ypres Salient behind to rebuild. The war ended on November 11th.

After the war, the town was rebuilt with money from Germany. The magnificent Cloth Hall was rebuilt exactly as it had been in the 1200s. The gothic St Martin’s Cathedral, originally built in 1221, was also rebuilt. Today Ypres maintains a close relationship with Hiroshima, Japan, another city destroyed by warfare. Ypres and Hiroshima work together to promote world peace.

The Walled City

Much of the great wall surrounding Ypres has been destroyed. Also, there used to be large towers at strategic places on the wall. The towers are no longer there, but you can see the circular hole where they used to be. However, a large portion of the wall remains today. Walking on top of it or passing through it at one of the gates or tunnels will show you its massive size and thickness. The wall is surrounded by an enormous moat that looks like a river. Despite the strong fortifications, Ypres could not always keep medieval invaders out.

This photo of a tunnel gives you some idea of the thickness of the wall.

The Menin Gate

During the time that Ypres had a wall completely around it, there were several gates. One of these was the Menin Gate. It was so-called because the road leads to the city of Menin on the French border. Another gate is called the Lille gate because the road goes to the city of Lille in France. By the start of the First World War, the Menin Gate was no longer a gate but simply a break in the wall with a bridge over the moat.

Click the first image to enlarge, then scroll to others.

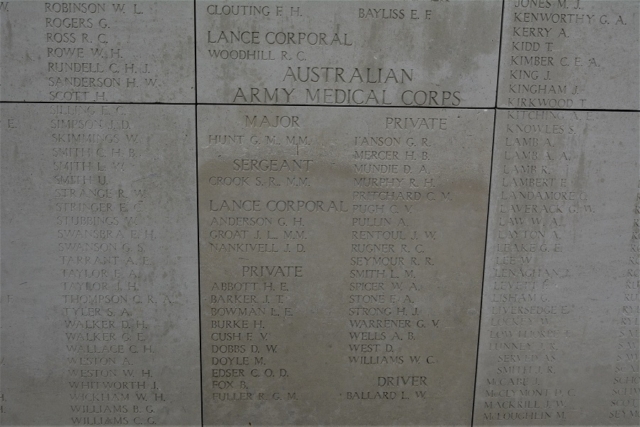

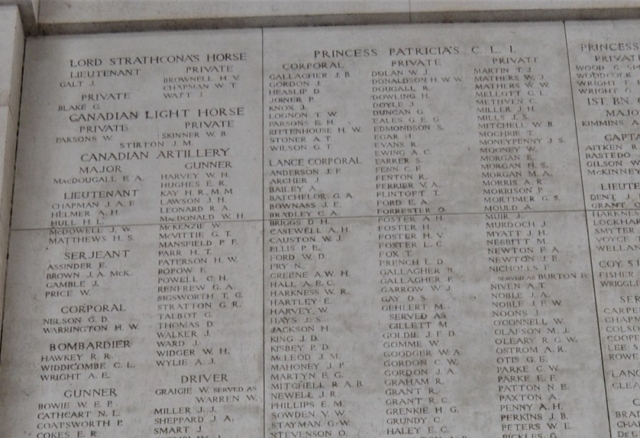

After the war, a colossal gate was constructed. This gate was not meant for defence. Instead, it was intended to be the world’s largest war memorial. On the walls of the gate are the names of 54,604 British Empire soldiers with no known grave. Thousands of soldiers disappeared in the waste-deep mud or were blown to pieces by artillery. Many lay on the battlefield for years because it was too dangerous to recover them. By the time the war ended, the bodies were unidentifiable. Some were buried, but the graveyard was later destroyed by artillery fire. Their friends buried some and the graves were never found. This is their memorial.

Bodies of soldiers killed during the First World War are still being found. If a soldier is found, identified, and buried in a graveyard, his name will be removed from the Menin Gate as it is a memorial only for those with no grave.

Of the 54,604 names engraved on the Menin Gate, 6,983 are Canadian.

After the Menin Gate was built, it was discovered that even though the gate is massive, there was not enough space for all the names of the missing soldiers. As a result, a further 34,957 British and New Zealand troops are not included on the gate walls. They are, however, inscribed on the memorial at the nearby Tyne Cot cemetery.

Canadian names of note on the Menin Gate:

- Three Victoria Cross recipients: Frederick Fisher, Frederick William Hall and Hugh McDonald McKenzie.

- Lt. Alexis Helmer, whose death inspired Lt.‑Col. John McCrae to write “In Flanders Fields”.

- Pte. John Smith (14th Bn Canadian Infantry): one of the youngest known casualties of Passchendaele, killed at the age of 15.

- Pte. Guiseppe Pitello (2nd Canadian Mounted Rifles Bn): the oldest known casualty of Passchendaele, killed at 56 years of age.

- Lt. Cameron Donald Brant (4th Bn Canadian Infantry): a descendant of famous Six Nations Chief Joseph Brant (Thayendanaga).

The Last Post

Canadians, British and people in other countries are very familiar with the Remembrance Day services held every 11 November to remember the sacrifice that their soldiers made during wartime. Not only the First World War but all wars, United Nations Peacekeeping duties, and other conflicts. In Ypres, the ceremony is to remember the soldiers who came from different countries and lost their lives in defence of their city.

Remembrance Day was celebrated at the Menin Gate on 11 November 1929 and every evening since then except during the Second World War when Ypres was occupied by the Germans who prohibited it. The ceremony began again on the very evening of their liberation on 6 September 1944. On the 9th of July 2015, the Last Post Association marked its 30,000th service.

The Last Post Ceremony at the Menin Gate. British soldiers on parade. (note the little girl of about ten years or less in the third row of the band).

Royal British Legion Colour Party on parade at the Menin Gate. Note the three flags are Great Britain, Belgium and Canada.

In Ypres, Every Day is Remembrance Day

The Last Post ceremony is held every evening at the Menin gate at 8 p.m. (20:00). I suggest you be there shortly after 7 p.m. (19:00) if you want a good view of the service. By 7:30, the crowd of spectators might be six deep. One day there was a huge crowd, and several more busses of students and tourists were still arriving. School bus trips from all over Belgium and the Netherlands are there most evenings.

Although the ceremony takes place daily, it is not always the same. Some days there will be a band and a parade. On other occasions, there will be a choir. Sometimes it is a simple ceremony with just the buglers and one person with a flag. On many days, there will be a piper.

Military regiments from British Commonwealth countries take turns providing troops for the parade. When I was there, British soldiers were in attendance. Likewise, you might see soldiers from Canada, Australia or other Commonwealth countries. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police have taken a turn doing the parade, as well as Air Force units. In May 2019, Canadian air and sea cadets did the honour guard.

You can check the Last Post website for their calendar of events. It shows the names of people and organizations laying a wreath and any particular service. The letters show if there will be a band (B), Choir (CH), or a Piper (P) in attendance. Last Post at the Menin Gate Calendar

The Menin Gate Lions

By the time of the First World War, the medieval Menin Gate was long gone. It has been replaced in more modern times with a simple gap in the wall to allow traffic to pass. Although there was no gate, since the mid-1800s, a pair of stone lions have been on guard at the location. This photo, taken before the First World War, shows the gap in the wall with the lions on either side.

During the war, the Menin Gate Lions were knocked off their pedestals and lost in the city’s rubble. They were not found until 1919 when they were placed in front of the ruins of the Cloth Hall.

After the First World War, the then major of Ypres gave the lions to the Australian government in appreciation of their contribution to the defence of Ypres. The lions are now guarding the entrance to the Australian War Museum and the Australian Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Canberra. I saw them there.

To celebrate the end of the First World War, 100 years later, in 2018. Australia loaned the lions to Ypres, and they were once more on guard at the Menin Gate.

The lions originally stood guard at the town hall starting in 1822. They were moved to the Menin Gate in 1862. Probably in the past 100 years, the existence of the Menin Gate Lions had been forgotten by most Ypres residents. Seeing them there on the 100th anniversary of the armistice incurred nostalgia for the lions. Ypres was very grateful for Australia’s part in the war, but, in my opinion, the lions should never have been given away. However, the town council supported the decision at the time. They are a part of the city’s heritage. However, they were a gift, and trying to get them back would be inappropriate.

The Menin Gate Lions are now back in Australia. However, the Australian government realized the importance of the lions to the city of Ypres. So, Australia created replicas of the famous lions and sent them to Ypres. They now stand on guard on either side of the Menin Gate. The reproductions were made in Belgium and paid for by the Australian government.

A nice souvenir of Ypres is a set of miniature Menin Gate Lions that look exactly like the originals. They are 8 cm (about 3 inches) in height. They are available at the Visitor’s Centre shop in the Cloth Hall.

Hooge and area

Hooge Museum

Just 16 km east of Ypres is the little village of Hooge. Here is an excellent WW1 museum located in a former church. The museum in Ypres has an emphasis on photos and personal experiences of the war. The Hooge museum is a more traditional museum that concentrates on displaying artefacts. This museum has tens of thousands of them. I liked this museum better than the one in Ypres. It is worth the time to go there.

The museum has everything from bayonets to a First World War Ford ambulance.

If you don’t have a car, buses go to Hooge from the Ypres town centre or the train station.

Hill 62

Hill 62 was important because there is a good view of Ypres from the top. It was behind Allied lines for the first two years of the war, but then it was captured by the Germans. On June 16th 1916, the Canadians set out to capture it.

Like they did later at Vimy in 1917, the Canadians used unusual artillery procedures never used before. The standard practice was to shell the area for days and then attack when the shelling stopped. But the Germans wait out the shelling in underground tunnels. When the shelling stopped, they came up to prepare for the attack. But the Canadians had a surprise for them. After the artillery shelling stopped and the Germans came out of their trenches, they shelled the area again instead of attacking. The artillery barrage started and stopped four times. By then, the Germans did not know what to expect when the Canadians finally charged and captured the hill.

This came at a cost of 1,200 Canadians killed and 4,500 wounded, mostly from the 4th Canadian Mounted Rifles and the PPCLI. The 4CMR had only 76 men left standing out of 702. A memorial at the top of the hill commemorated the Canadians in this action.

Hill 62 Museum

On the way to Hill 62 from Hooge, before reaching the monument at the end of the road, you will pass the Hill 62 museum. Like the one in Hooge, this is another excellent museum with many First World War artefacts.

The entrance to the Hill 62 museum also includes a visit to the extensive Canadian trenches and tunnels located in the woods behind the building. Click photos to enlarge.

Warning: These trenches have not been fixed up to make them suitable for tourists. They could be muddy, and the sides are made of now-rusty correlated metal with sharp corners. The tunnels are not lit, so bring a flashlight if you want to go in them. There are signs that the owners are not responsible for injuries.

Click the first photo to enlarge, and then scroll through them.

Sanctuary Wood Cemetery

Right next to the Hill 62 museum is the Sanctuary Wood cemetery, where the dead from the battle are buried.

You could walk from Hooge to Hill 62. It is about 1.5 km. There are tours from “Over the Top Tours” near the Menin Gate.

Passchendaele

Passchendaele (or Passendale in Flemish) is a town not far from the city of Ypres. It was just beyond the British front lines in German-held territory during the First World War.

There were three great battles for the city of Ypres during the war. The front line moved back and forth but not very far. At one time, it came very close to Ypres, but the Germans never captured the city. As a result, the British, French and British Empire troops were able to defend Ypres. But at a terrible cost in casualties, and the city was destroyed.

In the Third Battle of Ypres (also known as the Battle of Passchendaele), the Allies went on the offensive to capture Passchendaele and drive the Germans back. The conditions during the First World War were horrible, but at Passchendaele, they were horrendous. It was the wettest year since they began keeping records 70 years before. Imagine a land with no trees or even a blade of grass for as far as you could see. Imagine there is only mud and water, and people are shooting at you. You must dive into craters filled with waist-deep mud to avoid being killed. Many soldiers sank into the mud and were never seen again—especially those wounded who did not have the strength to get out. More than 54,000 soldiers simply disappeared, in addition to those killed and wounded.

The battle raged for more than three months. In the end, the Canadians captured the village of Passchendaele. There is a monument to the Canadians there.

Not far from Passchendaele there is a monument to the Nova Scotia Highlands (85th Bn) who took the lead in the Canadian attack and suffered the most casualties. They lost 391 of the 688 men in the battalion.

The British New Cemetery

The British New Cemetery is located near the village of Passchendaele. Many of the dead from the great Battle for Passchendaele are buried here, although many more are at Tyne Cot cemetery, which I will write about further on.

The New British cemetery has 2,101 graves, of which 1,600 are unidentified. These include 1,026 British soldiers including 894 unidentified, 292 Australians including 171 unidentified, 654 Canadians, of which 450 are unidentified, 126 New Zealanders, of which 83 are unidentified, and three from South Africa, of which two are unidentified. The photos above show three unidentified soldiers, one each from Australia, Canada and New Zealand. (click photos to enlarge).

Three Canadian soldiers were discovered during construction near Passchendaele in 2003 and are now buried here.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission is an organization that cares for all the British Commonwealth cemeteries worldwide. They look after 1.7 million graves in more than 23,000 cemeteries in 153 countries and more than 200 monuments. The Menin Gate memorial is one of them. Others include the Helles memorial in Gallipoli, Turkey and the Basra memorial in Iraq. (The Canadian government maintains the memorials at Vimy and Beaumont-Hamel as they are located in Canadian National Parks). The work of the CWGC is paid for by the six countries of Great Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa.

I have been to many of the CWGC cemeteries worldwide in my travels, including one in Hong Kong, where many Canadians are buried after a battle with the Japanese during the Second World War. All of these cemeteries are beautifully maintained and planted with flowers by a great team of gardeners. Go to any of them and see how lovely they are. Their work is a great show of respect for the soldiers who are buried in them.

You can visit their website at CWGC. Or, if you are in Ypres, they have an office near the Menin Gate. They will help you if you are looking for a specific grave.

The Tyne Cot Cemetery

Of the more than 23,000 cemeteries worldwide that the CWGC looks after, the Tyne Cot cemetery at Passchendaele is the largest, with 11,952 graves, of which 8,365 are unidentified.

There is a huge cross in the centre of the cemetery. The cross was built over the top of a German bunker which is now inside the base of the cross. An inscription on the cross says that the Australians captured this bunker (and two others in the cemetery) in 1917.

The cemetery has a huge wall around it (smaller at the back).

The Menin Gate was intended to be a memorial for all the British Commonwealth servicemen who died in the First World War and have no known grave. Although the gate is massive, they discovered afterwards that there was insufficient space for all the names. (It has 54,395 names inscribed on it of soldiers from Britain, Australia, Canada and other Commonwealth countries). The gate is missing the names of an additional 34,984 British soldiers and all 1,176 from New Zealand. Those soldiers not mentioned on the Menin Gate are inscribed here on the walls of the Tyne Cot cemetery.

The Victoria Cross

Citizens of British Commonwealth countries will know that the Victoria Cross is the highest and most prestigious of all military medals. It is awarded for extreme bravery in the presence of the enemy. Usually, the award of a Victoria Cross is presented by the British monarch at Buckingham Palace, although the medal can also be awarded posthumously. Receiving the medal is extremely rare. Only 1,358 medals have been issued since Queen Victoria introduced it in 1856.

Only 15 have been awarded since the Second World War, 11 to British soldiers and four to Australians. The winning of this medal also comes with a pension for life of 10,000 pounds per year for British Soldiers and $3,000 for Canadian and Australian soldiers. The amount increases periodically. The original amount in 1856 was ten pounds. The medals are extremely valuable. One was sold in England in 2009 for 1.5 million pounds. The medals are made from melted-down Russian cannons captured during the Crimean War (1854-1856).

I write about the Victoria Cross here because there are three medal winners in the Tyne Cot cemetery. The medal could be awarded to a living soldier, or it can be awarded posthumously. Another possibility is that after the award was made, the soldier might get killed in a later battle.

Lewis McGee was a sergeant in the Australian army. He was awarded the VC during a battle near Passchendaele. When his platoon came under heavy fire from an enemy machine-gun post, he charged the enemy position alone across open ground, armed only with a pistol and killed the machine gunners. He was later killed on 12 October 1917. He was 29—his medal is now in the Queen Victoria Museum in Tasmania, Australia.

Captain Clarence Jeffries, another Australian, was awarded the VC when he led his men in an attack that captured six machine guns and 65 prisoners before being killed. He was killed the same day as Sgt McGee, 12 Oct 1917. He was 22 (it says 23 on this tombstone, but he was killed 14 days before his birthday). Jefferies’ body was not found until 1920. When his wife died in 1964, she bequeathed his medal to Christchurch Cathedral in Newcastle, Australia.

The third recipient of the VC buried at Tyne Cot was a Canadian. Private James Robertson. When his platoon was held down by barbed wire and enemy machine guns, he rushed the enemy position alone, killed the crew and captured the machine gun. He then turned the gun around and used it to fire on the enemy while his platoon advanced. Later, when he was safely back in the trench, an enemy sniper shot two men out in the open. Robertson rushed out and carried the first wounded soldier back to safety. Unfortunately, he was killed while coming back with the second soldier on 6 November 1917. He was 34. (his tombstone says 35). His family still owns his medal. Most VCs have been sold or donated to museums after the owner died.

Tours of the Tyne Cot cemetery are available a few times per day. If you don’t have a vehicle, tours can be arranged by the “Over the Top” tour company, whose office is near the Menin Gate. While we were at the cemetery, there were five tour buses from Belgium, the Netherlands and Great Britain. It is the only cemetery I have ever seen with a visitor centre, toilets and guided tours and a huge parking lot for tour buses.

Battlefield Tours

Battlefield Tours are very popular. I have met people here from all over the world, including Canada and Australia.

Memorial Museum 1917

The Memorial Museum 1917 is located in a park in the town of Zonnebeke, which is about halfway between Ypres and Passchendaele. This is another good museum like the ones in Hooge and Sanctuary Wood. However, this one concentrates on the battles around Passchendaele in 1917 instead of the whole war. A visit to the museum also includes a walk-in trench system. Besides general displays of First World War artefacts, there are separate sections for each country involved in the war.

As you can see from the photos above, the museum has a great collection of artefacts, including uniforms, gas masks, helmets and weapons. They also have a fantastic collection of artillery shells, including poison gas shells (hopefully, they are inert). The last photo shows the trench system to which a visit is included with the museum tour. Click photos to enlarge.

PPCLI Memorial

Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry was the first Canadian infantry unit to enter the First World War on 21 December 1914. They fought in many battles, including Vimy Ridge and Passchendaele. Their monument is located near Ypres, where the PPCLI was on the front lines on 8 May 1915. The first two Canadians to be killed in the First World War were members of this regiment.

The monument is located just off highway N37 in the direction of Ypres but just before you reach the freeway A19. It is on Oude Kortrijkstraat.

St Julian, Canada Farm and Essex Farm

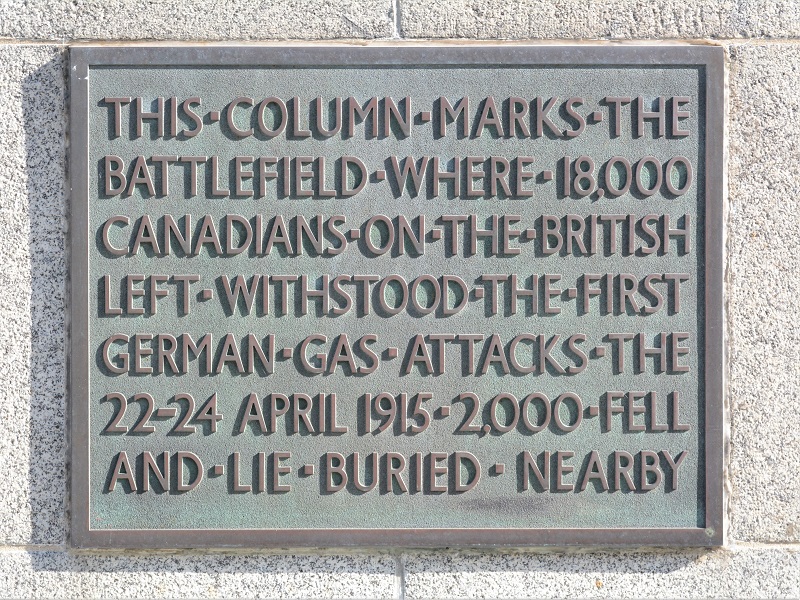

The Brooding Soldier

The Brooding Soldier monument is located in the town of Saint Julian (Sint Juliaan in Flemish), which is located west of Passchendaele. It was erected on the spot where the Germans first used chemical weapons. They fired 168 tons of Chlorine gas along a 6.5 km front. The area was defended by French, British, Canadian and Belgian soldiers. The French retreated after sustaining 6,000 casualties. Many died within minutes and many were blinded. Chlorine destroys soft tissue such as the lungs and eyes. The Canadians, British and Belgian soldiers stood their ground which was heroic but perhaps not very wise. They sustained 7,000 casualties, 2000 of them Canadians.

The gas attack created a gap in the Allied lines. The problem with using gas as a weapon is that it is indiscriminate and will kill the people who fired it as well as their enemies. Because of the gas, the Germans failed to exploit the gap in the line. The Allies discovered that urine neutralized chlorine. So the soldiers urinated on socks or handkerchiefs and held them over their faces. It sounds disgusting, but it worked, and the Allies held their ground and prevented a German breakthrough into the Ypres salient.

Canada Farm Cemetery

A cemetery called the Canada Farm British Cemetery is not far from St Julian. (I know the name does not make sense but keep in mind that at the time, Canada was part of the British Empire, and most people did not distinguish any difference between them). This is just a small cemetery, but I came across some graves of the Canadian Railway Troops and the Canadian Labour Corps, which I had not seen before. They were soldiers who were not fit for battle but were healthy enough to work on the railroad. They must have been building or repairing a railroad near here when they were killed by artillery fire. There are also some Newfoundlanders buried here.

Click photos to enlarge.

Essex Farm

Essex Farm is the name given to a farm located on the outskirts of Ypres on the banks of the Leper Kanaal (the Ypres Canal). Here the British and Canadians had a large encampment. They built bunkers into the hill along the canal bank to defend Ypres if the Germans ever got that close. There was also a military hospital here and a cemetery.

In Flanders Fields

Lt Colonel John McCrea was a Canadian military doctor working at the hospital at Essex Farm during the war. McCrea was very saddened when his friend, Alexis Helmer, was killed. This inspired McCrea to write the famous poem “In Flanders Fields”. This poem is read at every Remembrance Day service in Canada and other countries. Unfortunately, Helmer was never found, and his name is inscribed on the Menin Gate. Towards the end of the war, McCrea became very ill with pneumonia. He was evacuated back to England, but he never made it. He died on 28 January 1918 and is buried at Boulogne Sur Mer on the coast of France.

Statistics

The First Battle of Ypres was from 19 Oct to 22 Nov 1914. Casualties: British 54,000. Belgian 20,000. French 50,000. German 130,000.

The Second Battle of Ypres 22 Apr to 25 May 1915. Two hundred tons of poison gas were used. Casualties: Canadian 6,900. British 52,500. French 22,000. German one million.

The Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele) 31 Jul to 6 Nov 1917. British 310,000. Canadian 15,654. German 200,00.

Notes: There is a movie about the Battle of Passchendaele called, appropriately “Passchendaele”.